Thursday, March 31, 2022

How Pets Can Help Heal the Trauma of Parental Estrangement

Tuesday, March 8, 2022

Their Tails Kept Wagging: Pets Show Us How Hope, Forgiveness, and Love Prevail

Stephen’s quotes

Tuesday, March 1, 2022

Reconstruction of Bilateral Caudal Maxillectomy Using an Autogenous Auricular Cartilage Graft

Stephen J. Birchard

Rebecca L. Ball

History and Physical Examination

Jack was a 4-year-old neutered male golden retriever that presented for inspiratory stertor for several weeks. (Fig. 1)

|

| Fig. 1: Jack |

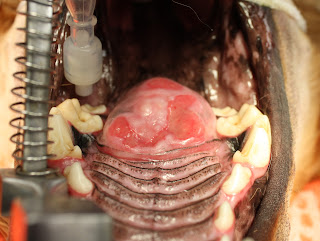

There was no other history of illness. On routine physical examination, no abnormalities were identified, but oral examination under sedation revealed a 4cm diameter firm circular mass in the caudal hard palate. (Fig. 2) The mass was not movable and extended the entire width of the hard palate between the molar teeth.

|

| Fig. 2: Caudal hard palate mass |

Diagnostic Tests

Plain film radiographs of the thorax revealed no evidence of metastasis. CT imaging of the oral cavity showed invasion of the bone of the hard palate and extension of the mass into the nasal cavity. A punch biopsy of the mass was obtained, and histopathology revealed multilobular osteochondrosarcoma.

Surgical Treatment

Under general anesthesia, the mass was excised by bilateral caudal segmental maxillectomy, including excision of the molar teeth on each side. After incising the mucosa around the mass and dorsal to the teeth, the maxillary bones and hard palate were incised with a bone burr and osteotome. The mass penetrated the hard palate but was not invasive into the nasal turbinates. The mass was excised, and bleeding was controlled with electrocautery and Vetspon in the nasal cavity. (Fig. 3)

|

| Fig. 3: Appearance of surgical site after resection of the mass. |

The large oronasal defect was closed by constructing bilateral mucosal flaps using buccal mucosa on each side of the defect and then sliding them to the midline. The flaps were closed on the midline in 2 layers: 4-0 PDS simple interrupted in the submucosa, and 4-0 PDS simple interrupted in the mucosa and sutured to the mucosa of the hard palate and soft palate in a similar manner. (Fig. 4)

|

| Fig. 4: Oronasal defect closed by bilateral buccal mucosal flaps. |

The mass was submitted for histopathology. (Fig. 5) Multilobular osteosarcoma (MLO) was confirmed, and complete resection with clean margins was reported.

|

| Fig. 5: Tissue specimen submitted for histopathology. |

Postoperative Care and Complications

Five days postoperatively, Jack presented for anorexia and a foul odor from the mouth. Oral examination revealed partial dehiscence of the rostral and caudal aspects of the buccal mucosal flaps, creating oronasal fistulae at both sites. Conservative management was initially recommended to feed soft food meatballs followed by mouth flushing with clean water.

Surgical Revision

The rostral oronasal fistula was repaired two weeks postoperatively using an autogenous auricular cartilage graft. Under general anesthesia, a 2 cm by 3 cm rectangular section of auricular cartilage was harvested from the inner leaf of the base of the left pinna. (Fig. 6)

|

| Fig. 6: Red rectangle indicates the approximate size and location of the harvested auricular cartilage graft. (This is not Jack but is a dog with similar size and anatomy of the ear pinna.) |

After lightly debriding and undermining the mucosa along the perimeter of the oronasal defect, the cartilage was placed in the defect with the edges inserted underneath the mucosa. The cartilage was sutured to the mucosa with 4-0 PDS simple interrupted pattern. (Fig. 7)

|

| Fig. 7: Closure of mucosa over cartilage graft (yellow arrow) and remaining oronasal defect (green arrow) to be repaired later. |

An esophagostomy tube was placed in Jack to allow feeding while bypassing the oral cavity.

Three weeks postoperatively, Jack presented to repair the remaining defect in his palate. The cranial defect had healed well over the cartilage graft. He was doing well with only occasional difficulty drinking water. Under general anesthesia, a hinged buccal mucosal flap was performed to close the caudal oronasal fistula. (Figs. 8)

|

| Fig. 8: Closure of hinged buccal/pharyngeal mucosal flap over remaining defect. (Arrow indicates the direction of the inverted flap.) |

Follow-up

Two weeks after this final reconstruction, Jack returned for a recheck examination. On oral exam, the flap was intact and healing well. (Fig. 9)

|

| Fig. 9: Healed defect after flap revision. |

Three months later, another recheck examination showed complete healing of all flaps and no persistent oronasal fistulae. Jack was doing well clinically with normal eating, drinking, and activity levels.

Jack lived 6 more years after his surgery to remove the MLO. He did well during that time with no issues related to his surgery and no tumor regrowth. He eventually died of causes unrelated to the MLO. Even with a prolonged recovery and multiple revision surgeries, the owners were pleased that they had pursued the treatment of Jack’s oral tumor.

Discussion

Bilateral segmental maxillectomy is a surgical option for oral neoplasia of the hard palate, mainly when the tumor is on the midline. Reconstruction is by creating bilateral sliding buccal mucosal flaps that are sutured to each other on the midline over the hard palate defect.

Dehiscence is common due to the tension across the incisions and the lack of underlying bone. Reconstruction of the resultant defect is challenging due to the scarcity of available local tissue. Autogenous auricular cartilage grafts have been reported to augment the closure of oronasal defects in dogs and cats. (1,2). This technique was effective in Jack repairing one of the defects in his mucosal closure. It provided a surface for the oral mucosa to proliferate and fill the oronasal defect. The remaining defect was judged to be too large to do an additional cartilage graft but healed with a hinged buccal/pharyngeal mucosal flap. The long-term results of the reconstruction surgeries were excellent. Further clinical studies are warrented to evaluate the auricular cartilage graft technique for other oral cavity disorders such as cleft palate.

Acknowledgment

Dr. Becky Ball was the primary surgeon in all procedures performed on Jack and directed his postoperative care.

1. Soukup JW, Snyder Cj, Gengler WR. Free Auricular Autograft for Repair of an Oronasal Fistula in a Dog. J Vet Dent, Summer; 26(2): 86-95,

2. Cox CL, Hunt GB, Cadier MM. Repair of Oronasal Fistulae Using Auricular Cartilage Grafts in Five Cats. Vet Surg 36:164-169, 2007.