October 16, 2007; a day I will never forget. I was in

between surgeries and taking a break in the hallway just outside of the

operating rooms at the veterinary hospital at Ohio State. I heard someone from

the other end of the hall call my name, and looked up to see Dr. Bob Sherding

motioning me to come look at something. He said excitedly: “You’re not going to

believe this; come look at these radiographs.” Thoracic radiographs of a dog

were on the view box in the treatment area. He was right, I couldn’t believe my

eyes. An arrow had pierced a dog’s chest and was completely through the heart. (Figs.

1-2)

|

| Fig. 1: Lateral thoracic radiograph of Josie |

|

| Fig. 2: Ventrodorsal thoracic radiograph of Josie |

Even more unbelievable was, the dog was alive and had just arrived at our

hospital. (Fig. 3)

|

| Fig. 3: Josie with arrow protruding from her thoracic inlet. |

The dog was being treated by the emergency service. She had

just been admitted and, remarkably, appeared to be in stable condition. A typical

Labrador, she wagged her tail as I approached her. No arrow through the heart

was going to affect the disposition of this friendly retriever. The arrow was

protruding out of her thoracic inlet and was bouncing up and down in the same

rhythm as her heart beat. Her vital signs were all normal, and she was

alert and responsive.

We did not know her name at this point. A friend of the hunter who shot the arrow took her to Drs. Steven Sawchek and Rhonda Masterson. They immediately referred the dog to Ohio State and one of their technicians drove her there. She was a 1 year old in tact

female yellow Labrador. The Ohio State students decided she should be called

“Cupid” until her real name was later discovered, which was “Josie”.

Supportive care was begun on Josie and some diagnostic tests

immediately performed. An echocardiogram (Fig. 4) confirmed that the arrow was

indeed completely through her heart and had penetrated the right and left

ventricles.

Routine blood tests did not reveal any significant abnormalities. Josie was taken to the anesthesia prep area, placed under general anesthesia and prepped for surgery. (Fig. 5)

|

| Fig. 4: Echocardiogram showing the arrow (indicated by arrows) inside the heart. |

Routine blood tests did not reveal any significant abnormalities. Josie was taken to the anesthesia prep area, placed under general anesthesia and prepped for surgery. (Fig. 5)

|

| Fig. 5: Josie under anesthesia during the aseptic preparation of her chest cavity |

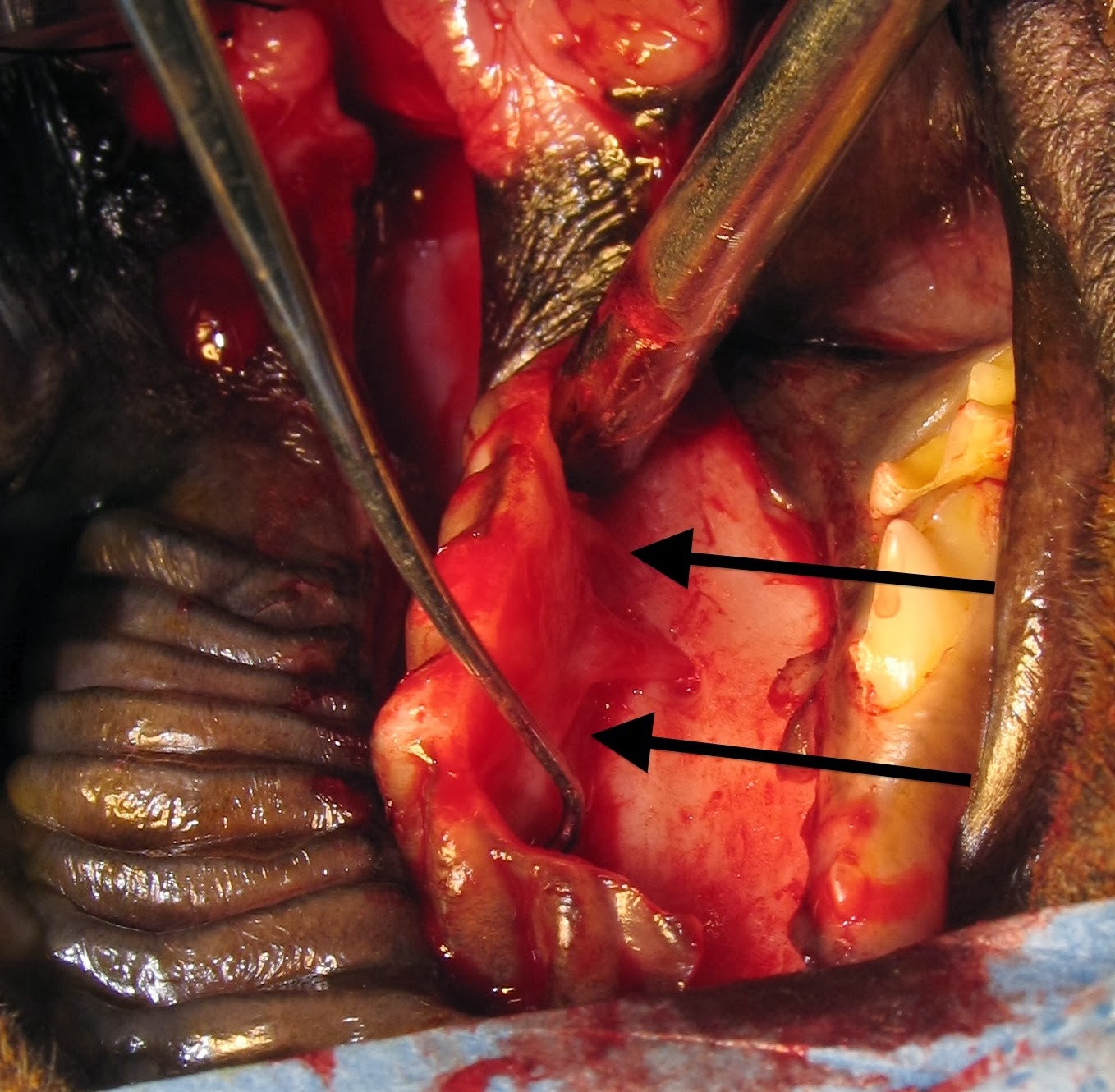

We performed a median sternotomy to allow exposure of the

entire heart. (Fig. 6)

The arrow could be clearly seen entering the right

ventricle and exiting the left ventricle. (Fig. 7)

No lung lobes had been

punctured, and the tip of the arrow stopped just short of the diaphragm. There

was no blood in the pleural cavity and the heart was not bleeding from the

arrow punctures. The arrow was acting like a cork, sealing the heart muscle and

preventing hemorrhage.

|

| Fig. 6: Performing the sternotomy with an oscillating bone saw. |

|

| Fig. 7: Intraoperative photographic of Josie's heart. Cranial is to the left. The arrow is seen protruding from the left ventricle (arrow) |

A pericardial sling was performed by opening the sac,

placing stay sutures and anchoring them to the Finochietto retractor. This

elevated the heart toward the sternum improving exposure. Now for the difficult

part. How do we extract the arrow from the heart without causing catastrophic

hemorrhage? After some quick discussion with my resident and the other doctors

in the room, I decided to place a purse string suture of 3-0 PDS around the

exit site of the arrow in the muscle of the left ventricle. The arrow was then backed out of

the left ventricle by pulling from the cranial aspect, and the purse string was

tightened as the tip of the arrow went inside the heart. A small jet of

hemorrhage occurred even after tightening the suture, so an additional simple

interrupted suture was placed to control the bleeding. Very little blood was

lost and Josie continued to do well under anesthesia. The same suture type was

placed in the right ventricle and the arrow then completely removed.

A thoracic drain tube was placed, the sternotomy closed

routinely and Josie moved to ICU for recovery and further care. She was kept on

a continuous ECG, her PCV monitored, and she was treated with analgesics,

antibiotics, and antiarrhythmics. She had a systolic murmur since there was a defect in the

ventricular septum created by the arrow, but her cardiovascular parameters were

otherwise normal.

Josie did very well and was discharged 3 days

postoperatively. Two weeks after surgery she came in for suture removal. She

was doing well and thoracic radiographs showed no abnormalities. (Figs. 8-9)

The systolic murmur was still present however.

|

| Fig. 8: Lateral thoracic radiograph of Josie 2 weeks postoperatively (The sternotomy was closed with wire). |

|

| Fig. 9: Ventrodorsal view of the thorax on Josie 2 weeks postoperatively |

About 3 months after surgery Josie came back to Ohio State

for ovariohysterectomy. On physical examination no abnormalities were found and

no cardiac murmur was present on auscultation. A repeat echocardiogram

confirmed that the ventricular septal defect had healed. I asked my student if

it was ok for me to scrub in with her on this spay since this was kind of a

special case. The surgery went well and Josie was discharged the following day.

|

| Josie just before release from the hospital |

I can honestly say this was the most incredible case I have

ever treated. How can a dog

sustain an arrow completely through the heart and live to tell about it? I am

not a hunter but I’m told that the arrow that penetrated her was a “field tip”

rather than a “broad head” arrow and that’s why she survived. The tip of the

arrow is the same diameter as the shaft. Thus, the shaft was able to seal the

holes in the cardiac muscle and prevent hemorrhage.

Long Term Follow Up

Dr. Sawchuk recently spoke with Josie's owner. She is now 10 years old and still doing well. Here is a recent picture of her. What a beautiful dog she is.

|

When seriously ill pets are surrounded with love, they are more likely to survive. Read about this, and Josie's complete story, in Dr. Birchard's new book: "Their Tails Kept Wagging". Click here for more information.